CQRS Frameworks: The Good, the Bus, and the Ugly - Part 1

Master ASP.NET Clean Architecture with MediatR in Part 1 of our CQRS series. Future posts will explore alternatives like Brighter, MassTransit, and Wolverine.

Imagine this: you deliver an MVP that wows your client. PostgreSQL, ASP.NET 10, React—you nailed it. Everything seems perfect… until you check your backend. It’s a tangled web of classes and services.

Time to fix it with Clean Code Architecture. Sounds simple, but now you face a choice: which framework should handle the Mediator layer? MediatR looks ideal… until you hit licensing issues. Suddenly, the search for alternatives begins. This post will guide you through the options and help you pick the right one—without getting lost in the spaghetti.

The Goal of this Article

This guide presents the Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) pattern, explaining its principles and benefits. It also covers the Mediator design pattern and its role in enabling decoupled component communication. Additionally, it provides step-by-step instructions to set up a project architecture following Clean Code principles using the MediatR library to implement these patterns. In later parts though, we will also take a look at some alternatives to MediatR. The setup targets new developers unfamiliar with this architecture, expanding their knowledge and suggesting frameworks for future use—especially as other parts of this blog are published (stay tuned!). Experienced developers can use this post as a reference for specific code blocks or descriptions, like an encyclopedia.

With that being said, you may have this question…

What is CQRS and why would I need it?

As a software developer, you’ve likely noticed that reading and writing data are fundamentally different tasks. That’s the core idea behind CQRS, which stands for Command Query Responsibility Segregation. This design pattern separates operations that change state (commands) from those that retrieve data (queries).

Imagine building an ASP.NET Web API for an e-commerce platform. In a traditional CRUD architecture, you’d use the same model and service layer to create, update, and fetch orders. With CQRS, you define a dedicated command object - like CreateOrderCommand - to encapsulate the intent to create an order. This command is handled by a specific handler responsible for validation, business logic, and persistence. Retrieving order details is handled by a separate query object, such as GetOrderDetailsQuery, processed by its own handler focused on efficient data retrieval and returning a tailored DTO.

This separation offers several benefits. First, your codebase becomes cleaner and easier to navigate, since each class has a clear responsibility. Second, you can optimize read models for performance without complicating write logic. Third, commands and queries are easy to test in isolation, making your application more robust. Finally, CQRS enables scaling reads and writes independently, which can be crucial in high-load systems.

In practice, CQRS fits well into ASP.NET projects when paired with MediatR, a popular library that mediates between controllers and handlers. Instead of calling services directly, controllers send commands or queries through MediatR, which dispatches them to the appropriate handler. This keeps controllers lean and logic well-encapsulated.

CQRS isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. For small, simple applications, it might be unnecessary. But as your project grows and domain logic becomes complex, CQRS offers a scalable, maintainable architecture built to last.

To help you visualize this, the diagram above shows how commands and queries flow through an ASP.NET Web API using MediatR, each with its own handler and model. If you’d like, I can walk you through a sample project structure or help refactor an existing solution to adopt CQRS.

Okay. Now we know about CQRS but this still bears the following question…

What exactly is a Mediator?

As a software developer, you’ve likely built components that need to talk to each other. A button click needs to update a form, a service needs to notify another service, or a UI element needs to react to a change in another. What happens when many components need to interact? You often end up with a tangled web of dependencies where every object holds a direct reference to every other object it affects. This "spaghetti code" is brittle and hard to maintain. That’s the core problem the Mediator pattern solves.

Imagine a complex "Create Order" dialog in your application. You might have a dropdown for the product, a text box for the quantity, a checkbox for "gift wrap," and a "Submit" button.

- Changing the Product dropdown might need to update a "price" label.

- Changing the Quantity text box also needs to update the "price" label.

- Checking the Gift Wrap box needs to update the "price" label and maybe show a new text box for a gift message.

- The Submit button must be disabled until a valid product and quantity are entered.

Without a Mediator, each control would need to know about all the other controls it interacts with. The quantity box would need a reference to the price label, the product dropdown would need a reference to the price label, and the submit button would need references to all the other controls to check their state.

With the Mediator pattern, the controls (we call them colleagues) don't know about each other. They only know about one central OrderFormMediator object.

- When the quantity changes, the text box simply tells the Mediator, "My value is now 5."

- The Mediator encapsulates all the business logic. It receives that message and then commands the other components: "Price label, update yourself. Submit button, check if you should be enabled."

- The controls are "dumb" and decoupled; all the intelligence lives in the Mediator.

This approach offers powerful benefits. First, it promotes loose coupling. Your UI controls (or services) are no longer tightly bound, making them much easier to reuse and modify. Second, it centralizes interaction logic. Instead of hunting through ten different component classes to debug an interaction, you look in one place: the Mediator. This dramatically simplifies maintenance and makes complex logic easier to understand. Third, it improves testability, as you can test components in isolation by providing a mock mediator, or test the complex interaction logic by testing the mediator class directly.

Like any pattern, Mediator isn't a one-size-fits-all solution. For very simple interactions between just two components, it can be unnecessary overhead. But as your application's interaction logic grows, the Mediator pattern provides a clean, maintainable, and decoupled architecture for managing that complexity.

With that out of the way, I think it is time to start with our little project, to show how it is done.

Project Setup

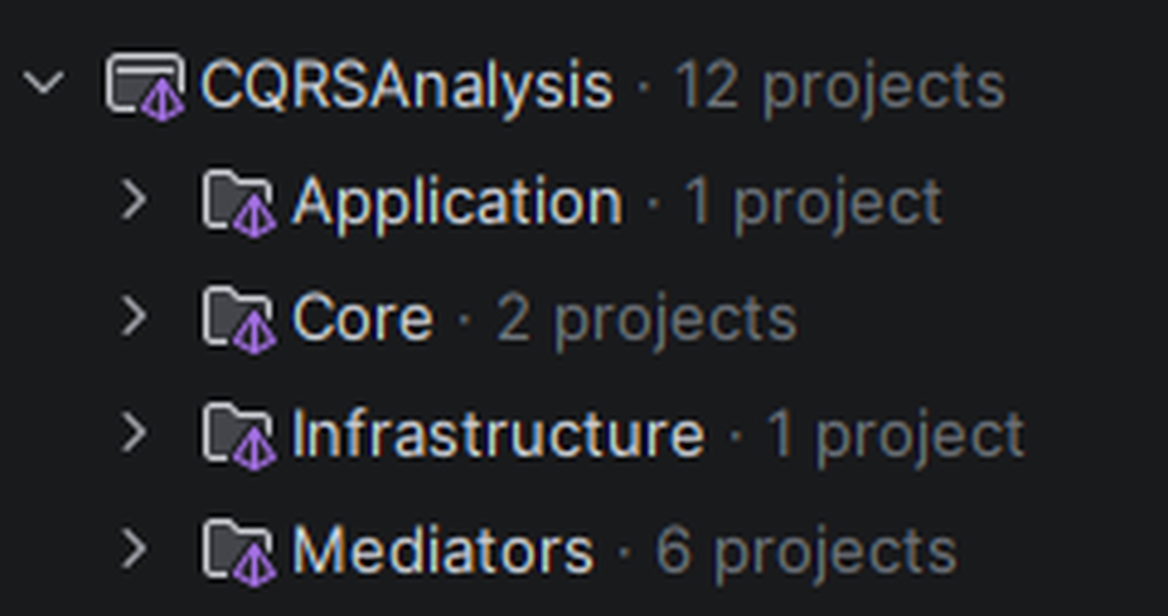

To begin, create a simple Blank Solution named CQRSAnalysis. This solution will contain all our projects, as a Clean Code Architecture project should. To organize within our IDE, I added Solution Folders to separate concerns like Hosting, Business Logic, and Persistence. It looks like this:

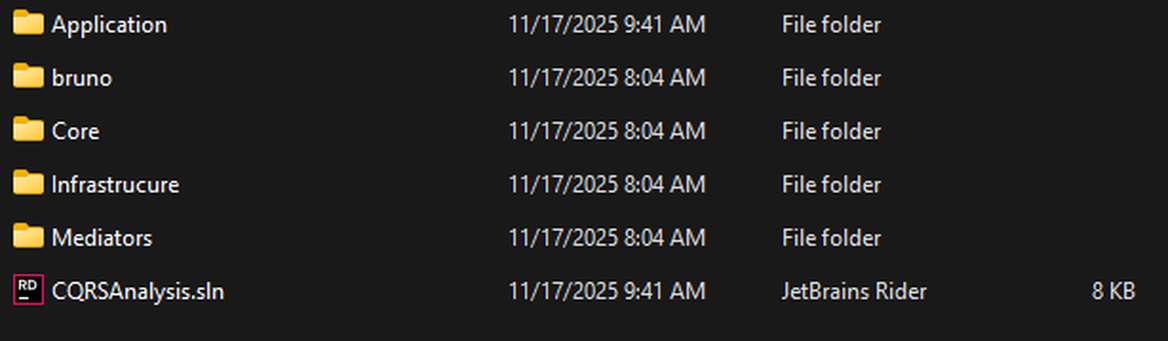

To also resemble this structure in our explorer, I also created these folders outside of the IDE:

Don’t worry about the bruno folder. It holds requests for “Bruno,” an open-source Postman alternative that lets you store requests in files and add them to your VCS.

Okay, so we got our basic structure done and are now able to start coding! So let’s start with our Contracts and Services in the Core Layer!

The Core Layer

To begin, we create our first Class Library to hold Entities. Under Core, add a new Class Library named CQRSAnalysis.Domain and a Class called Item. The Item has a required name and quantity. To keep it simple, we won't use an ID property and will designate the name as the entity's primary key in the database.

public class Item

{

public required string Name { get; init; }

public int Quantity { get; set; }

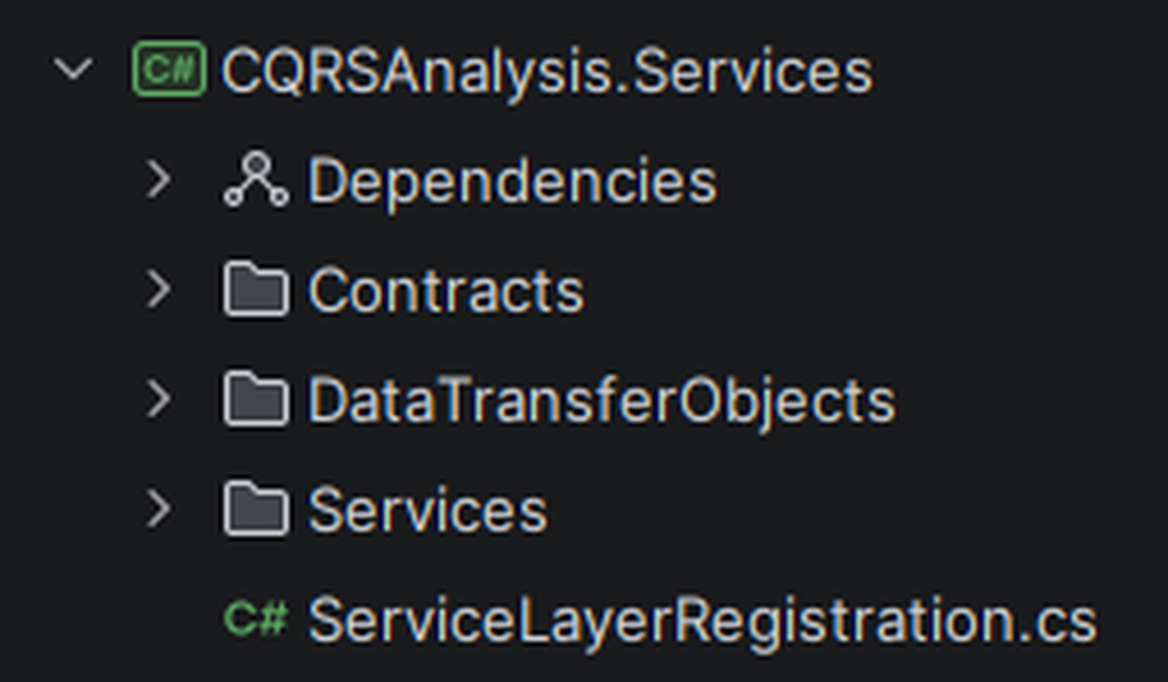

}This will be the only class inside our Domain project, keeping it simple. Next, create a new Class Library called CQRSAnalysis.Services. This library will contain our service and repository contracts, the service implementations, and Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) to avoid sending actual entities. We also need a class to handle service registration for our IoC Container, named ServiceLayerRegistration. To organize it well in our IDE, create folders for interfaces and classes:

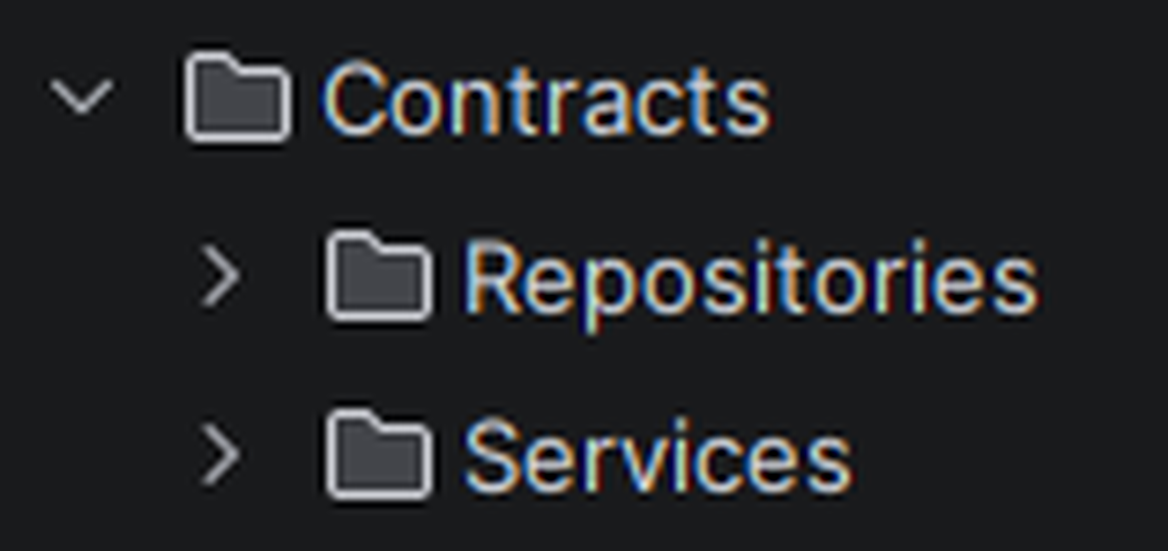

In our Contracts folder, create two sub-folders named Services and Repositories. These correspond to the folders in the Services project and the Persistence project.

In the folder DataTransferObjects, create a new class called ItemDto. It will mirror our Item entity but serve as a request object. Recall Clean Code Architecture best practices: an entity should only be accessed within its persistence project.

public class ItemDto

{

public required string Name { get; set; }

public int Quantity { get; set; }

}Let's start with our first repository interface. It defines simple repository functions for demonstration. You can add your own functions and explore this structure's features. The repository class will be called ItemRepository to match the entity it handles, so we create the interface IItemRepository.

Declare these methods inside the repository:

public interface IItemRepository

{

IQueryable<Item> GetItemList();

Task AddItemAsync(Item item, CancellationToken cancellationToken);

}These methods retrieve all items from the database or add a new entry to the Items table. Next, create a new interface in the 'Services' folder under contracts and name it IInventoryService. This service handles business logic and calls IItemRepository to query the database. The IInventoryService interface includes two functions like the repository, but they accept DTOs instead of entities and return lists of DTOs instead of queryables of entities.

public interface IInventoryService

{

Task<List<ItemDto>> GetItemListAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken);

Task<int> AddItemAsync(ItemDto item, CancellationToken cancellationToken);

}Great, now we can implement the interface. In the Services folder, create a class named InventoryService that implements the IInventoryService interface. Implement the methods as you wish; for demonstration, I will keep it simple without error handling. Also, inject the IItemRepository interface into the constructor to access our database.

public class InventoryService(IItemRepository itemRepository) : IInventoryService

{

public Task<List<ItemDto>> GetItemListAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var itemQuery = itemRepository.GetItemList();

return itemQuery.Select(x => new ItemDto(){ Name = x.Name, Quantity = x.Quantity }).ToListAsync(cancellationToken);

}

public async Task<int> AddItemAsync(ItemDto item, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var entity = new Item()

{

Name = item.Name,

Quantity = item.Quantity

};

await itemRepository.AddItemAsync(entity, cancellationToken);

return item.Quantity;

}

}Of course, this looks extremely simplified and could be done in a better manner. For example you could use a Mapper framework like Mapperly, instead of directly creating new instances of ItemDtos or Items!

With that done, we simply need to register the service in our ServiceLayerRegistration:

public static class ServiceLayerRegistration

{

public static IServiceCollection AddBusinessLogic(this IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddTransient<IInventoryService, InventoryService>();

return services;

}

}Cool, this means we are done with the core of our application, which handles all business logic. This means we now need to implement our Infrastructure Layer, or else we won’t be able to store data into a database for example. So let’s start with that next!

The Infrastructure Layer

With the Core layer complete, we can focus on the Infrastructure layer. This layer of Clean Code Architecture handles communication with external systems—such as REST APIs, gRPC, real-time communication via SignalR, and more. In our case, it connects to the database, resulting in the persistence layer.

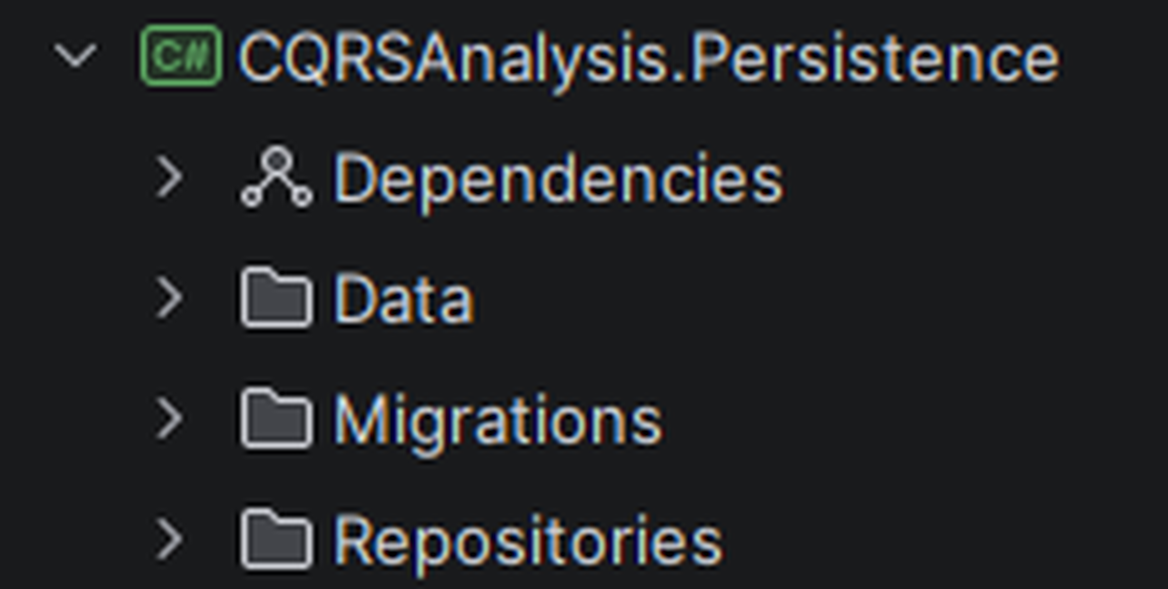

To get started, create a new project called CQRSAnalysis.Persistence and create new folders inside of it like so:

To use EF Core with Postgres, add the package Npgsql.EntityFrameworkCore.PostgreSQL via dotnet add package Npgsql.EntityFrameworkCore.PostgreSQL. This also adds transitive packages like EntityFrameworkCore, our ORM. Create a class named PersistenceRegistration to register repositories and DbContexts. In the Data folder, create InventoryDbContext. This DbContext accesses the database, contains DbSets for tables, and entity configuration. With only the Item entity, it has one DbSet and one entity configuration for the primary key, the item name.

public class InventoryDbContext(DbContextOptions<InventoryDbContext> options) : DbContext(options)

{

public DbSet<Item> Items { get; set; }

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder)

{

modelBuilder.Entity<Item>(entity =>

{

entity.HasKey(e => e.Name);

});

base.OnModelCreating(modelBuilder);

}Now, create a new class called ItemRepository that implements the IItemRepository interface. Remember to reference the Services project and inject the InventoryDbContext. I'll keep it as simple as possible like before:

public class ItemRepository(InventoryDbContext context) : IItemRepository

{

public IQueryable<Item> GetItemList() => context.Items.AsQueryable().AsNoTracking();

public async Task AddItemAsync(Item item, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

context.Items.Add(item);

await context.SaveChangesAsync(cancellationToken);

}

}The GetItemList method retrieves a queryable list of Item entities from the database, using the AsNoTracking method to improve performance by not tracking changes to the entities as well as only allowing read access to the entities. The AddItemAsync method takes an Item object and a CancellationToken as parameters. It adds the item to the Items DbSet of the context and asynchronously saves the changes to the database.

Now let’s register our repository and DbContext in our PersistenceRegistration class:

public static class PersistenceRegistration

{

public static IServiceCollection AddPersistence(this IServiceCollection services, string connectionString)

{

services.AddDbContext<InventoryDbContext>(options =>

{

options.UseNpgsql(connectionString);

});

services.AddTransient<IItemRepository, ItemRepository>();

return services;

}

}Finally, create a migration for our DbSet and its configuration. EntityFrameworkCore knows how to set up the database when applying migrations. Run this command in a terminal inside your persistence project folder: dotnet ef migrations add Initial --project .\CQRSAnalysis.Persistence.csproj --startup-project ..\..\Application\CQRSAnalysis.API\CQRSAnalysis.API.csproj

We are one step closer to completing our setup and can now create the application users would interact with. This will be done in the next step.

The Web API

With our Core and Infrastructure layers complete, we can create our first application host. I use an ASP.NET 10 Web API, assuming you are reading this blog post from a backend developer's perspective. It includes all dependencies for Dependency Injection setup out of the box, which makes the next steps much easier.

To be able to use our layers, we need to reference them in our project:

<ItemGroup>

<ProjectReference Include="..\..\Core\CQRSAnalysis.Services\CQRSAnalysis.Services.csproj" />

<ProjectReference Include="..\..\Infrastrucure\CQRSAnalysis.Persistence\CQRSAnalysis.Persistence.csproj" />

</ItemGroup>With them added, we should be able to register our layers and make use of them further on. Here is my Program.cs file as an example:

using CQRSAnalysis.API.Extensions;

using CQRSAnalysis.BrighterDarker;

using CQRSAnalysis.CQRSlite;

using CQRSAnalysis.MassTransit;

using CQRSAnalysis.MediatR;

using CQRSAnalysis.Persistence;

using CQRSAnalysis.Services;

using CQRSAnalysis.Wolverine;

using CQRSAnalysis.WolverineHttp;

using Wolverine.Http;

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddBusinessLogic();

builder.Services.AddPersistence(builder.Configuration.GetConnectionString("Demo"));

builder.Services.AddControllers();

// Learn more about configuring OpenAPI at https://aka.ms/aspnet/openapi

builder.Services.AddOpenApi();

var app = builder.Build();

// Configure the HTTP request pipeline.

if (app.Environment.IsDevelopment())

{

app.MapOpenApi();

}

app.MapControllers();

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.RegisterHandlers();

await app.ApplyMigrationsAsync();

app.Run();You may notice line 36: await app.ApplyMigrationsAsync(); is an extension method I wrote to apply all migrations from our persistence project:

public static class HostExtensions

{

public static async Task ApplyMigrationsAsync(this IHost host, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

using var scope = host.Services.CreateScope();

var context = scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<InventoryDbContext>();

await context.Database.MigrateAsync(cancellationToken);

}

}With our project set up, we can begin analyzing CQRS frameworks and gain hands-on experience. For starters, we will take a look at MediatR, since it is more or less state-of-the-art in the .NET community, but in later parts we will explore some alternatives. Enjoy!

You can find the source code of this blog here: https://github.com/totallynotgeorg/cqrs-blog-analysis

MediatR

What is MediatR?

MediatR is a widely recognized and popular modern CQRS framework that supports the Clean Code architecture. It was created by Jimmy Bogard, who is also the developer behind the well-known AutoMapper library. In April 2025, Jimmy made the decision to monetize his frameworks specifically for enterprise users, which is a reasonable and understandable choice given the effort involved in maintaining such projects. He introduced a Multi-Licensing model: hobbyists, non-profit organizations, and companies with revenue below a certain threshold can continue to use the framework freely, provided they sign up on his website to obtain a license key. However, some organizations and developers who previously relied on MediatR because it was completely free may now start to look for alternative solutions due to this change.

From a technical perspective, MediatR emphasizes simplicity and ease of use. To register it within our API, it only requires a single call to the IServiceCollection.AddMediatR() method, which is available through the NuGet package. This setup enables the use of the IMediator interface, as the ASP.NET Inversion of Control (IoC) container manages all dependencies at runtime via Dependency Injection. This design makes integrating MediatR straightforward and aligns well with modern development practices.

The Setup

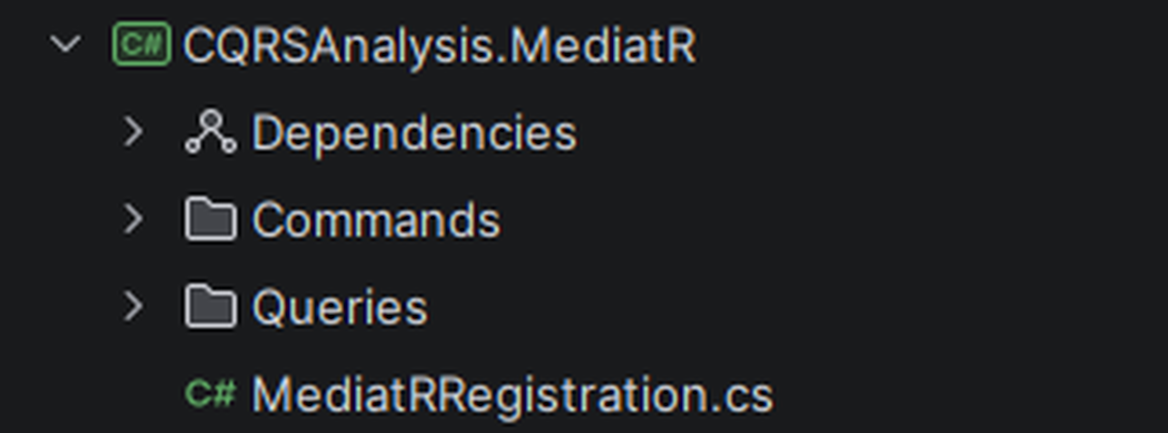

For demonstration, I created a new Class Library in my solution called CQRSAnalysis.MediatR. It includes all classes needed to register MediatR to our API, as well as Commands and Queries to call our service functions.

First things first. In our new project, we will create a new class called MediatRRegistration, which will be a static class and consists of only one static method. This will be an extension method of the IServiceCollection interface, so we can call it in our API when registering our services.

public static class MediatRRegistration

{

public static IServiceCollection AddMediatRServices(this IServiceCollection services, string licenseKey)

{

services.AddMediatR(config =>

{

config.LicenseKey = licenseKey;

config.RegisterServicesFromAssembly(typeof(MediatRRegistration).Assembly);

});

return services;

}

}I added a parameter for the license key, required to use MediatR, which passes to my MediatR configuration. The API provides this key from its appsettings.json file or, in my case, the secrets.json file, since I want to avoid committing keys or other secrets to GitHub. The second configuration tells MediatR where to find our handlers. The easiest way is to use C#'s typeof keyword and the .Assembly property. The framework then scans for and registers the handlers during startup.

Great, now let's register MediatR to our API by calling builder.Services.AddMediatRServices(builder.Configuration.GetValue

This registers MediatR, allowing us to use its interfaces when handling incoming requests to our endpoints.

Next, let's create a handler to process API requests. I created solution directories inside my Class Library: Commands and Queries. These separate requests into write (Commands - POST/PUT/DELETE) and read (Queries - GET) operations. For example, in an Inventory Management System, to add items, I might have a Command called AddItem, and to get all items, a Query called GetItemList. We could also create Commands like DeleteItem or UpdateItem and Queries like GetItemByName or GetItemById. But we will keep it simple to give an overview of the proposed frameworks. So this is what the project structure then will look like:

Inside those folders, we will create classes for Commands/Queries and their Handlers.

The AddItemCommand

I'll start with the AddItemCommand and its AddItemCommandHandler, allowing us to add items to our inventory. The AddItemCommand class will also serve as the request model in our Controller, at least for the POST endpoint. This command requires Name and Quantity properties, which the user must include in the request.

public class AddItemCommand : IRequest<int>

{

public required string Name { get; init; }

public int Quantity { get; init; }

} You may notice that the Command implements an interface called IRequest

With the command created, we can now focus on the Command Handler. This class implements the IRequestHandler

public class AddItemCommandHandler(IInventoryManagementService service) : IRequestHandler<AddItemCommand, int>

{

public Task<int> Handle(AddItemCommand request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var quantity = service.AddItem(new Item()

{

Name = request.Name,

Quantity = request.Quantity

});

return Task.FromResult(quantity);

}

}We can use Dependency Injection in our handlers because we registered them in our IoC container via the extension method we wrote earlier and used in our Program.cs file. Here, we inject the IInventoryManagementService interface, allowing us to call the AddItem function and pass a new Item with the request's properties.

Since we now have a functioning command, which creates items in our inventory, we will also need a query to retrieve the items from our inventory. This will be done in the next step.

The GetItemListQuery

The Query is relatively straight forward - just like with our command, start with a new class called GetItemListQuery and implement the IRequest

public class GetItemListQuery : IRequest<IList<ItemDto>>

{ }As you may notice, we don’t need any properties, since this query will respond with a list of items. Of course if you have a lot of items in your inventory, you may want to use properties like Skip, Take, GroupBy or anything similar, which would enable you to use a feature called Paging for your frontend - but this is a topic for another time.

Since we also need a Handler for this query, let’s implement that as well:

public class GetItemListQueryHandler(IInventoryService service) : IRequestHandler<GetItemListQuery, IList<ItemDto>>

{

public async Task<IList<ItemDto>> Handle(GetItemListQuery request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var items = await service.GetItemListAsync(cancellationToken);

return items;

}

}And with that, our GetItemListQuery is done and we can now set our focus on creating Endpoints and making our first requests!

Making a request

Now, inject the IMediator interface into our controller and use the IMediator.Send method to send the request to the bus, where MediatR routes it to the appropriate handler.

[Route("api/mediatr")]

[ApiController]

public class MediatRItemController(IMediator mediator) : ControllerBase

{

[HttpGet]

public async Task<IActionResult> GetItems(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var items = await mediator.Send(new GetItemListQuery(), cancellationToken);

return Ok(items);

}

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> AddItem(AddItemCommand command, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var quantity = await mediator.Send(command, cancellationToken);

return Ok(quantity);

}

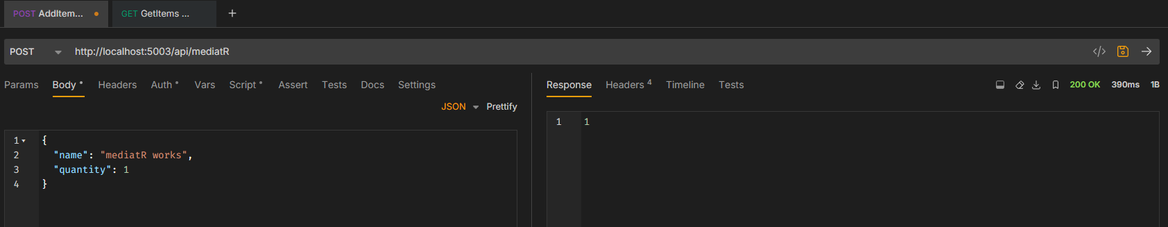

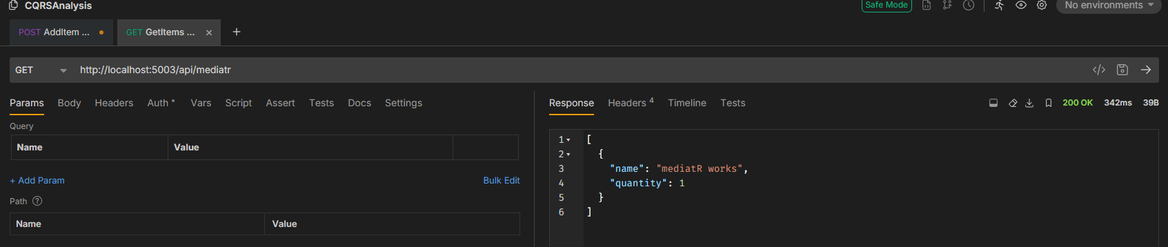

}The pictures below show that requests are processed as intended, allowing us to add items to our inventory and retrieve the item list.

With that we are done. Congratulations, you now have a functioning Clean Code Architecture with MediatR as your chosen CQRS framework. In the next part we will do something similar with a framework called Brighter/Darker and will then compare this alternative to MediatR.